The “Common Heritage of Humanity” is an ethical concept and a general concept of international law. It creates that some localities belong to all humanity and that its resources are available for the use and benefit of all, taking into account future generations and the desires of developing countries. It planned to create common spaces and resources, but it can apply beyond this traditional area.

When it was mainly introduced in the 1960s, the “Common Heritage of Humanity” (CHM) was a controversial concept today. This controversy contains scope, content, and status issues, along with CHM’s relationship to other legal ideas. Some commentators consider it old-fashioned due to its lack of use in practice, such as the extraction of resources from the seabed and its subsequent rejection by modern environmental treaty regimes. On the contrary, other commentators consider it a general principle of international law with enduring significance.

Increasing global ecological degradation and the continuing inability to stop the so-called calamity of the commons (Hardin 1968) will guarantee the continued relevance of the concept of the commons, despite the complications surrounding its receipt by states. Evidence for this can find in various efforts to apply CHM to natural and cultural heritage, marine living resources, Antarctica, and global ecological systems such as the atmosphere (Taylor 1998) or the climate system.

Table of Contents

Origins of the Principle of the Common Heritage of Humanity (CHM)

The CHM legal discussion usually begins with the Maltese Ambassador Arvid Pardo’s (1914–1999) speech to the United Nations in 1967. This speech planned that the seabed and ocean floor beyond national jurisdiction be considered CHM. This main event triggered the subsequent negotiation of the 1982 Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS III) and other legal developments that subsequently earned Arvid Pardo the title of “father of the law of the sea”.

Then CHM has a much longer history, and Pardo built on this to develop CHM as a legal concept for the oceans. Other people, including the writer and ecologist Elisabeth Mann Borgese (1918 – 2002), saw CHM as a central ethical concept for new world order, based on new forms of cooperation, economic theory and philosophy. This story is essential to elucidate the moral core of CHM: the charge of humans to care for and defend the environment, of which we are part, for present and future generations.

A draft World Constitution of 1948 provided that the Earth and its resources would be the common property of humanity. They administered for the good of all. Concern over nuclear technology and resources for military and peaceful purposes also led to an initial proposal that nuclear resources be collectively owned and managed and not owned by any state. Traces of CHM are also established in the UN Outer Space Treaty (1967), which governs state examination and use of outer space, the moon, and other celestial bodies. CHM, however, rose to prominence in the context of the evolution of the law of the sea. The 1967 World Conference on Peace through Law referred to the high seas as “the common heritage of mankind” and declared that the seabed should be subject to the jurisdiction and control of the United Nations.

Core Elements – Common Heritage of Humanity (CHM)

There is no concise, fully agreed-upon definition of CHM. Its features depend upon the facts of the rule applying it or the space/resource to which it uses. There are several core elements, however:

- No state or person can own collective heritage spaces or resources (the principle of non-appropriation). They can remain used but not kept, as they are a part of the international heritage (inheritance). And therefore belong to all humankind. It protects the global commons from expanding jurisdictional claims. When CHM smears to areas and resources within national jurisdiction. Sovereignty is subject to specific responsibilities to keep the common good.

- The use of common heritage will remain used following a cooperative management system to benefit all humanity, i.e., for the common good. It has interpreted as creating a type of trustee relationship for the explicit protection. The interests of society slightly than the interests of particular states or private entities. The CHM will derive active and equitable sharing of benefits (including financial, technological, and scientific). It provides a basis for limiting public or private commercial uses and prioritizing distribution to others. As well as developing states (intragenerational impartiality between present generations of humans).

- CHM shall remain kept for peaceful purposes (avoiding military uses).

- CHM will remain passed on to future generations under substantially intact conditions (protection of ecological integrity and intergenerational equity between present also future generations of humans).

In current years, these core elements have ensured that CHM remains central to the efforts of international environmental lawyers. It recognizes and articulates many critical components of sustainability.

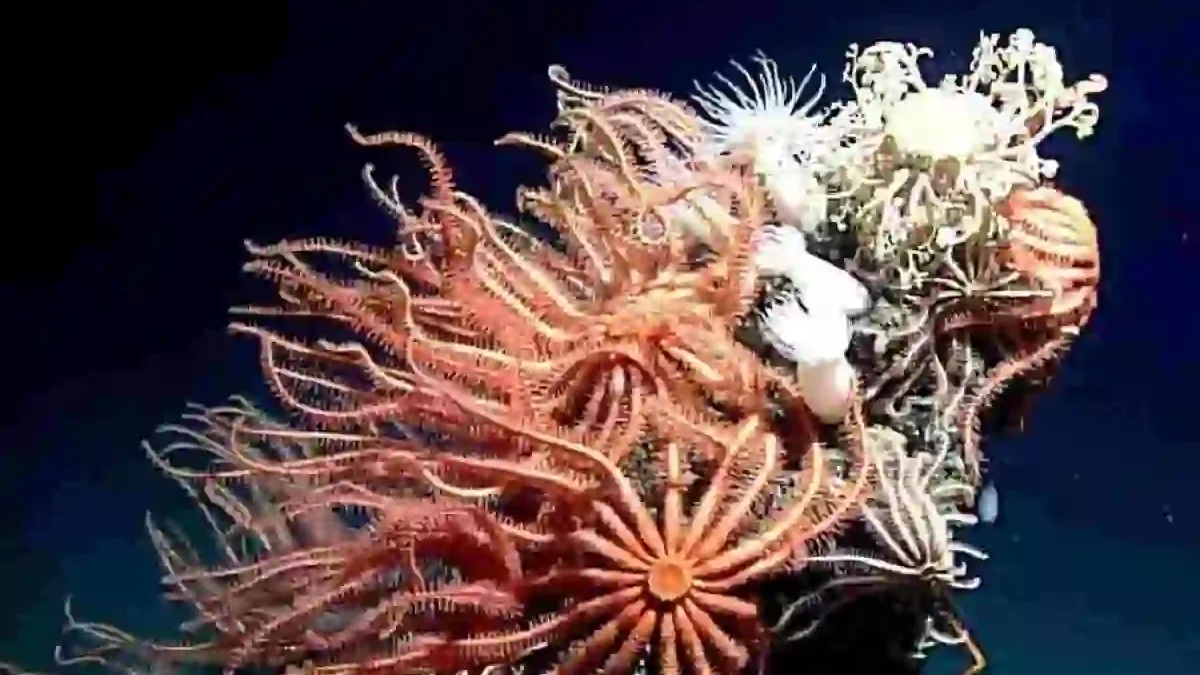

Extended Applications

Over the years, CHM has applied to various resources and spaces: fisheries, Antarctica, the Arctic landscape. The geostationary orbit, genetic resources (the genetic material of plants, animals and valuable life forms) essential food resources. In current years, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Has strongly supported CHM through a wide range of initiatives. For example, declarations, conventions and protocols, that recognize heritage natural and cultural as CHM. Although hard to define, “natural and cultural heritage” includes both tangible and intangible elements. Ranging from archaeological sites and historical monuments to cultural phenomena (such as literature, language and customary practices). And natural systems that include islands, reserves of biosphere and deserts. A new potential application area is the human genome. For example, it can prevent corporate interests from patenting the human genome.

In a biological and generational context. It is possible to contend that the Earth itself is a global common good shared by each group and that CHM should “extend to all-natural and cultural resources. Wherever they find, that are internationally important to the world. well-being of future generations “.